"Animation isn't the illusion of life; it is life."

With a career as expansive and groundbreaking as Chuck Jones' it is nearly impossible to figure out an entry point or narrowed focus. The Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies years would be an obvious point, but that's roughly thirty-years and hundreds of cartoons. Jones began his life at Termite Terrace, the beloved nickname of the animation department at Warner Brothers, in 1933 as an assistant animator, was promoted in 1935 to animator, and again in 1937 as a director. I suppose you could winnow it down to just the big ones - "Duck Amuck," What's Opera, Doc?" or "One Froggy Evening," for example - but that would cause his smaller jewels to become blind spots.

A hybrid treatment would be the best option, but there's not enough space here for that. So, instead, I'm focusing in on his post-1962 work. Why his major works post-1962? Because that's when Jones was fired from Warner Brothers after they discovered his work on Gay Purr-ee, mainly as a screenwriter though the designs display his trademark angles and curves.

Some of his best work was yet to come, including adaptations of Rudyard Kipling and Dr. Seuss. Doesn't mean that there won't be appearances by Bugs Bunny and company, Jones was far too entwined with that particular franchise to ever be removed from it entirely, but they won't be the bulk of the focus/material. Robin Williams famously dubbed him "the Orson Welles of cartoons" while presenting his honorary Oscar in 1996, and it's an apt comparison as Jones broke the mold of what an animated short could be.

Instead of going in chronological order and bouncing around the various types of works, this essay will be grouped by type. Here we go. Get comfortable because it is expansive.

TV SPECIALS

Adventures of the Road Runner

Beginning life as a failed TV pilot, Adventures of the Road Runner was eventually released as a theatrical short, before finally getting chopped up into three further shorts. Taken individually, everything here is a wonderful piece of animation, filled with smart gags and a frantic go-go-go pacing. All of it taken together without the benefit of commercial breaks leaves a certain feeling of a padded out running time.

This becomes most obvious when the Adventures of the Road Runner goes meta-textual in its humor. We pull back to see that the cartoons we're watching are part of a TV show watched by two young boys. One of them is Ralph from "From A to Z-Z-Z-Z," a little daydreamer with a rich imaginary life, and the other his unnamed friend who tries to psychoanalyze him. This leads to "From A to Z-Z-Z-Z" being spliced into the proceedings as an example of Ralph's inability to concentrate leading him to identify with the Road Runner's constant buzzing about. "From A to Z-Z-Z-Z" is an absolute delight, a charming blast into an elementary school child's fervid imagination, but it has absolutely nothing to do with the exploits of Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. Its inclusion feels like narrative padding, try as the writer’s might to throw in a reason behind it.

Where Adventures of the Road Runner excels is in the newly created shorts. The revelation that Wile E. Coyote videotapes all of his exploits with the Road Runner in an effort to strategize and analyze weaknesses in his plans is a fun joke, sold by Mel Blanc's tongue-in-cheek egg headed vocal intonations for Wile E. Coyote. The presence of reused footage from older cartoons feels more organic here, and the effect overall works far better.

The gag where the Road Runner barrels across a bridge so fast he warps it in his wake, dragging several cacti along for the ride, and setting up a bit of physical violence-as-punchline that the Looney Tunes do so damn well is a solid chuckler. This is what can be said for this elaborately constructed collage-as-TV pilot as a whole work. It's filled with solid chuckles that the film-makers know how to do well, it's just a shame that the middle feels unnecessarily padded out with extraneous bits that don't fit in with the whole.

How the Grinch Stole Christmas

This is twenty-five minutes of absolute perfection. A hugely successful artistic marriage between the adapter and source material, How the Grinch Stole Christmas is as much of a mighty, towering classic as the beloved Dr. Seuss book.

For me, this is perennial viewing. Christmas is never quite complete without a few viewing experiences every year – A Charlie Brown Christmas, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, and this, which may be my favorite of the lot. Jones and Seuss merge beautifully, balancing out the weirdness and idiosyncrasies in each other's work to create something vital and wonderfully alive.

No offense to Ron Howard's 2000 live action version, but this is the only one you'll ever need to watch. It's a model of absolute economy, moving through the story with a fantastic balance of pacing, merging in moments of humor, darkness, song, and joyous uplift in a bite sized chunk.

Even better is the sense of enthusiasm and love for the source material that radiates throughout the special. Jones clearly finds a kindred spirit in Seuss' topsy-turvy, angular world. Whoville is free of straight lines, made up entirely of curves, sharply jutting out corners, and rolling hills and valleys. The basic framework allowed Jones to really go crazy with the whacky character movements and designs, creating smart, unique choices like the Grinch's eyes hauntingly peering out of a chimney or the montage of Whos running around putting up decorations with a large assortment of gadgets and gizmos.

But would How the Grinch Stole Christmas be quite as memorable without the vocal intonations of Boris Karloff? He gravels his voice for the Grinch, reaching back into his Universal Monsters days to bring weight and menace to the role, and narrates with his naturally soft, lilting speech, finding the humor and warmth in the text in his delicate tones. I'll fight anyone who disagrees with me on this, but I find his work here to be among the greatest of his career.

Matching him in virtuoso vocal delivery is Thurl Ravenscroft's booming bass voice singing, "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch." Ravenscroft delivers the series of jokes and verbal put-downs like a great radio ham. He knows this is faintly ridiculous material, but he delivers it like it's a piece of the great American songbook. In fact, it would be easy to imagine Karloff and Ravenscroft delivering this as a radio play, and achieving the same delirious heights on the listener without the vibrant animation and colors to go along with it.

It's a merger of many great talents on a top-shelf project, and we were blessed with a masterpiece. I've loved this special for my entire life, and the older the I get the more I appreciate its combination of vibrancy, quirk, and hint of darkness before delivering the heartwarming and uplifting final bow. I said it earlier, and I'll say it again, this is perfection.

The Pogo Special Birthday Special

The creative tension and falling out between comic strip creator Walt Kelly and Jones mares The Pogo Special Birthday Special. It's like listening to an orchestra playing while being ever-so-slightly off key the entire time. The backgrounds are lively and colorful, the character models are appealing, and there's a few good verbal jokes, but the pacing is all over the place, and at times it drifts too far over into either Kelly or Jones territory to congeal as a coherent collaboration. There's also the general problem of something so southern in nature given life by people clearly unfamiliar with the sounds and vibes of the locale, as too many of the voices sound like goofy riffs on dialects instead of cohesive character voices. Jones' trademark wit is gone, and the entire thing is too cutesy for words. Something went wrong, or the major fight between the two of them caused the rest of the production to rush out a finished product. Not the worst thing Jones attached his name to (check the Raggedy Ann and Andy Christmas special), but it is disappointingly shapeless.

Horton Hears a Who

Whereas 1966’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas is a model of pacing and narrative economy in adapting a piece of children's literature, Horton Hears a Who is a slightly bloated affair. Too many songs slow things down, and perhaps there just wasn't enough story here to justify a full twenty-five minute special. Still, it's Chuck Jones adapting Dr. Seuss and that by definition already has quite a bit going for it.

Mainly the sweetness and gentleness of Horton is quite pleasing as a hero. He's a kind soul, trying to do what's right while the entire jungle gossips and ostracizes him. Hans Conried goes uncommonly gentle in giving him life. Conried was typically called upon to give blustery life to over-the-top villains, like the melodramatic Captain Hook or the Mathemagician. Jones also indulges in his cutesy tendencies here, giving Horton large, soft eyes complete with long eyelashes and a rounded body held atop wonky knees.

And the pleasing angularity of several of the characters and backgrounds works well to contrast against Horton's curvature. Jane Kangaroo, the primary antagonist, is particularly smart as a character design. Haughty, imperious and borderline fascist in her beliefs, Jane leers at Horton's "odd" behavior, turning the entire jungle against him. June Foray finds a cinched, tough vocal cadence; rounded tones and clipped phrases abound, to give Jane a preening, queenly villainy.

It's bright and colorful, and perhaps if you're young enough the heavy messaging will be easily forgiven, but Horton's lack of subtlety with its imparting is exhausting. Once the narrative starts rolling it never ceases to remind of us of its moral, rolling out "a person is a person, no matter how small" every few minutes. By design there must be a happy ending, but the about-face of the jungle denizens in Horton is quite shocking. They go from planning to boil the flower, caging Horton, and threatening him to softening, marveling at how Horton was right all along, and then parading off into the sunset. The tonal whiplash is astounding and nowhere near as earned as the Grinch’s, who had an entire act based around his redemption and not mere seconds.

Horton Hears a Who is still far better than many of the live action atrocities and CGI animations that take Dr. Seuss' work as a springboard for post-modern deconstruction. This one is the obvious weaker piece between the two Jones made, and probably would have been better served as an animated short. I can't say it's bad, because it’s not, but it is frustratingly sloppy.

The Cricket in Times Square

Between 1973 and 1975, Jones produced three specials based upon The Cricket in Times Square by George Selden. This first entry plays the story straight, complete with an ending that feels somehow rushed upon given the leisurely pace of the rest of the piece.

There’s a quietness and gentle spirit at work here, something you just don't find any longer in children's entertainment. The story is a simple urban fairy tale, a family's newsstand in the subway near Times Square is having trouble generating business, and a cricket from the countryside accidentally gets transplanted there. The cricket befriends the young son of the family, along with a streetwise mouse and urbane cat, and the three critters plot to help the family's fortunes. The cricket is revealed to have a wonderful gift for music, and this proves the key to changing the family's financial woes.

There’s a quietness and gentle spirit at work here, something you just don't find any longer in children's entertainment. The story is a simple urban fairy tale, a family's newsstand in the subway near Times Square is having trouble generating business, and a cricket from the countryside accidentally gets transplanted there. The cricket befriends the young son of the family, along with a streetwise mouse and urbane cat, and the three critters plot to help the family's fortunes. The cricket is revealed to have a wonderful gift for music, and this proves the key to changing the family's financial woes.That's it, that's the entirety of the story, no cynicism, no snark, just heartfelt lessons about how music can be a bridge between different people and helping others. The art is more sophisticated here than your typical Jones work up to this point, with human figures looking more realistic, and animals appearing more grounded than the elongated shapes and loose limbs of his more famous work. Jones also made the choice to hold back on showing the faces of the humans until late in the running time, using their wide-eyed wonder and expressions of joy primarily in the climax, which finds the cricket performing his final concert and all of Times Square pausing to take in the beauty of the music. It's a wonderful bit of flourish in this urban fairy tale.

Shame then that right after this ebullient moment the story quickly winds down with the next scene being one in which the father takes the cricket on the train to Connecticut to release him back into the wild. This thread, of the cricket yearning to go back home, is introduced early, then quickly brushed aside in favor of Mel Blanc's Tucker the Mouse cracking jokes alongside Les Tremayne's haughty purrs. It’s not a fatal flaw, as everything that came before it is strong, but it's just a weird bit of pacing. Still, of the three Cricket specials, this is the strongest and most satisfying.

A Very Merry Cricket

Picking up right where The Cricket in Times Square ends, A Very Merry Cricket reunites us with Tucker the Mouse and Harry the Cat on a story that’s part road trip and part lukewarm variation of How the Grinch Stole Christmas. New York City, introduced through a nightmare hallucination of location zooms and disembodied voices, is filled with anxiety and anger about the Christmas season, and these two think Chester's magical musical abilities are just the remedy the city needs.

Subtle in its emotional manipulations this is not, taking the same morale as The Grinch but delivering it with chainsaw-through-Jell-O nuance. A Very Merry Cricket is far more fun when it's plotting is shaggy, and we simply hangout with Harry and Tucker in their misadventures. Jones' humor shines in some of these gags, and an alley cat character feels like a more regulated cousin of a Looney Tunes character. Luckily, most of the special is taken up by their road trip adventures, and the anti-commercialism of the holidays is regulated to the very beginning and the very end. Not quite as overlooked or even-handed as the prior installment, A Very Merry Cricket is still a highly enjoyable romp.

Yankee Doodle Cricket

Between 1975 and 1976, much of America's pop culture ephemera was drunk upon the upcoming bicentennial. Don't believe me? Well, then look no further than the third and final installment in the Cricket specials, Yankee Doodle Cricket. Purporting to tell the unknown truth about the American Revolution, this special finds Chester, Tucker, and Harry recast as Revolutionary players helping the cause along.

The special opens with Tucker in the library reading a book called Oddities in American History, and that about sums up this installment, an oddity. While A Very Merry Cricket lacked the sophistication and general overlooked nature of the first one, this one feel reasonably slept on. It's hopelessly dated as a relic of the bicentennial fever striking the country.

There's still plenty of chuckles to be found here, but the surrounding narrative is weak. Let's focus on the jokes for a moment, a rattlesnake with a head cold asks Tucker to not tread on him, inspiring the infamous drawing and slogan. Or Harry giving his opinion to Thomas Jefferson about the first lines of the Declaration of Independence, a flurry of quotes from future Presidents can be heard as they’re discarded. Yet Jones feels somehow disconnected from much the material here, with the bright spots shining brighter than the fussiness surrounding them.

Rikki-Tikki-Tavi

1975 ended the Cricket series, but it also launched the three Rudyard Kipling adaptations that Chuck Jones made between 1975 and 1976. These three specials are among the best of Jones' work, capturing both the darkness of the original stories and providing a template for Jones' artistry to go wild. (No pun intended.)

The first of these three specials, Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, is twenty-five minutes of sheer excellence from top to bottom. The simplicity of backgrounds and shapes jettisoned here in favor of a more realistic animation style. I never knew traditionally animated cobras could be so frightening, but between the menace of Orson Welles and June Foray's vocal intonations and their ominous, supple animation, that's exactly what I thought in these moments.

Even better is the stylistic choices to display Rikki-Tikki-Tavi's swiftness, as his entire body transforms into elongated lines, stretching and shrinking back to its natural size. It's a hypnotic effect, and put into great effect during the numerous scenes of tension and danger in which Rikki fights with the snakes antagonizing his adopted family. This body warping effect is also used in moments of mischief and discovery, used for more comedic effect in these moments, but working just as well.

Jones perfectly captures of feeling of Kipling's work, bringing out both the charm and the danger lurking beneath the surface. Much of Welles' narration is straight from the text, and Welles' voice caresses around the lines beautifully. His origins in radio drama makes him a perfect voice actor for animation, and this only makes one wish he did more of it. Jones was smart to bring him in, just as he was smart enough to know when to play the story straight and when to get flashy in his artistic choices.

Introducing the villain, Nag the cobra, as an inky black blob undulating against the bright sun alerts us to the stakes that will unfold as the story progresses. We begin in simplistic, cutesy methods, with Rikki playing cute and sweet and getting more ferocious as we go along. Even better is the shock of colors (red, yellow, and white) that flash across the screen during Nag's death scene with only the pattern of his hood remaining clearly visible. The tensest moment comes late in the story as Nagaina, the female cobra, threatens to strike against the human child that Rikki has befriended. No flashy animation tricks here, just still human characters, a patient cobra, and Foray's disturbed voice work that sounds like her chords were sandpapered heavily before she walked into the recording booth.

I remember watching this several times as a child, and it still holds up. It’s one of his late-period masterpieces, and one of the best Jungle Book adaptations. As scary as it is enchanting, Rikki-Tikki-Tavi is a wonderful piece of work.

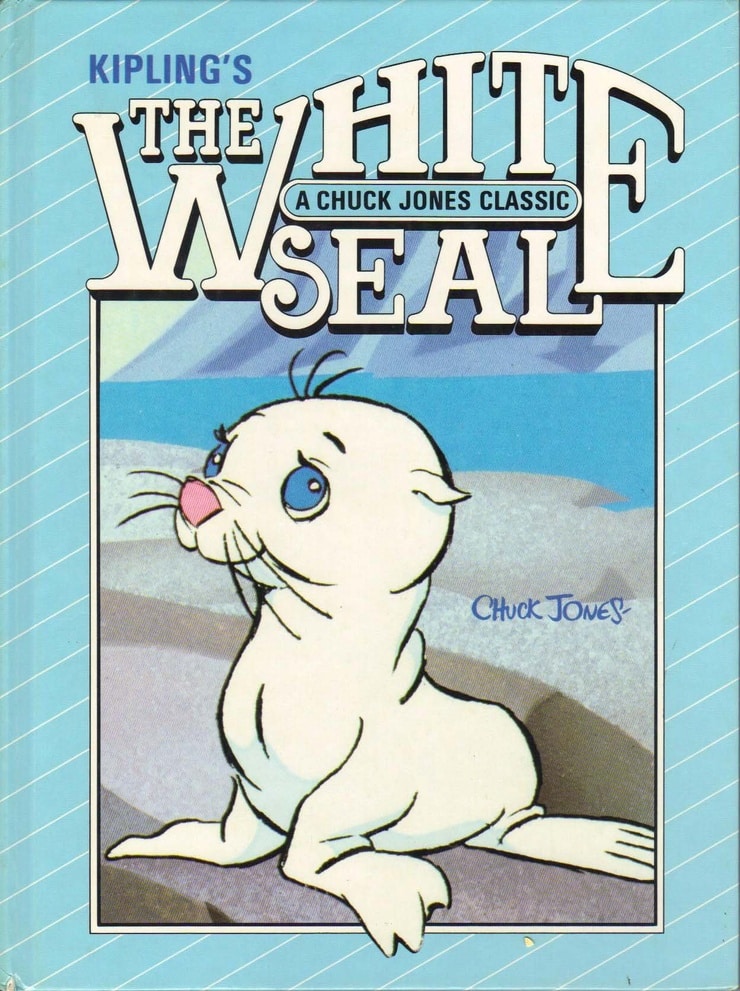

The White Seal

A few months after Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, Jones once again returned to the world of The Jungle Book with this version of "The White Seal." Two-thirds of his Kipling trilogy consists of the more obscure tales from that classic tome, and that's partially why I appreciate them so much. There's also the simple fact that The White Seal is just a beautifully animated, completely engaging work.

These Kipling adaptations feel different from much of Jones' more popular work as they're more mature and slower paced. They're less reliant upon physical humor and filled with palpable moments of dread and tension. The first one in The White Seal comes from watching a young Kotec chased by a shark, but a vast majority of the tale is occupied by his venture to find a new home where they'll be free of the humans.

Naturally, he encounters several underwater denizens, both friendly and cruel. None of these encounters are as cruel as the ones with mankind. A scene of Kotec staring in horror as the humans hunt down and kill many of his fellow seals shies away from showing the act itself, but through clever visual choices and Kotec’s expression we still get the intensity of the moment.

And I haven't even begun to describe the look of the piece. The character animation is fluid and dynamic, with personalities evident in their movements. A scene where a young Kotec meets a whale is a small marvel, as bubbles distort his face as they float across the frame. What's even more interesting is how Kotec goes from cute and cuddly, looking like the big eyed critter you'd find in any children's cartoon to a more realistic representation, so too does the rest of the piece. Kotec ages before our eyes by repeatedly leaping out of the water, appearing larger and fuller with each joyous dive.

The backgrounds point towards Jones' love of the abstract, as Nova Scotia is all geometric patterns of white and blues, and ocean waves are green lines under the water. The island paradise that Kotec discovers is made up of large chunks of colors, with little detail work. These bright colors and simplistic shapes give The White Seal a buoyant feeling that is quite effective for the piece. Same can be said for Roddy McDowell's airy vocal work as both Kotec and the narrator. A slight step-down in artistic achievement from Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, The White Seal is still a wonderful work in Jones' extensive output.

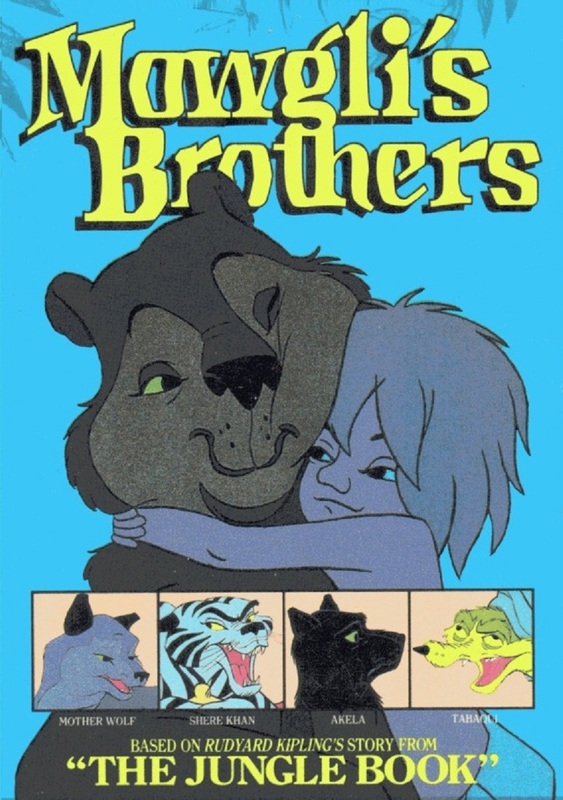

For his final dip into Kipling's work, Jones decided to tackle the biggest character, and the first story, in The Jungle Book, Mowgli. Nothing against Disney's film version, but Jones' television specials are clearly the superior versions. There's no need to describe the story, as you're already familiar with it from any of the numerous incarnations of the tale, but Jones' version sticks closest to the text, restoring characters and relationships to their rightful places after Disney's mutations of them.

Jones' love for the source material bristles throughout his three Kipling shorts. Perhaps it's how pliable they were to the animated form, allowing Jones to explore and expand what a children's cartoon could look and feel like. It's certainly true that Mowgli's Brothers displays an artistic maturity that several other cartoons of its type don't.

This version enchants me from the opening credits straight through, where Shere Khan is made up of black triangles stalking across a hot pink background, to the end, where Mowgli tries to return to the man village. If the backgrounds in The White Seal were abstract, then the ones here are the vaguest of impressions. An angular jungle of jagged shapes and rounded figures that looks more like the impressions and imaginings of a bright child than a typical cartoon.

June Foray and Roddy McDowell return to vocal duties, and Foray is particularly warm and maternal here. McDowell gets the bulk of the work here, and he gives a full array of vocal styles to the various characters and a clipped, posh accent for his moments of narration. Much like Welles in Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, McDowell wraps his delicious vocal intonations around Kipling's text with aplomb.

The poetry of Kipling is brought to life by Jones in Mowgli's Brothers, both in the narration and in the experimentation of the piece. Taken individually, any of the adaptations are beautifully crafted wonders, but taken all together they're something even greater. Each with a unique look and tone, each possessing individual strengths, they form an array of colors and sounds that push the boundaries of what American animation can look like and be. But how many people still watch them? I feel as if they're criminally underrated and overdue for a reappraisal and place of prominence in Jones' work.

Raggedy Ann and Andy in The Great Santa Claus Caper

It's a bit hard to review this mess as there's not much there to speak about. The plot makes zero sense, even going by the wide margins of which we accommodate Christmas specials tied to merchandised characters, and the whole thing consists of only a handful of scenes with little in the way of wit or creativity that sparkles in the best of Jones' work.

Raggedy Ann and Andy in The Great Santa Claus Caper begins with a breaking of the fourth-wall by a Wil E. Coyote dollar store knockoff, Comet the Reindeer overhearing his ramblings, and deciding that the best backup for this mission are a pair of rag doll siblings. It's idiotic and muddled from the outset, with nothing is truly at risk here. Jones did better work tackling the behemoth of Christmas and its emotional meanings years earlier, and subsequent dips into the same well turned up increasingly drier results.

At least the gentleness and quietness of Johnny Gruelle's work was translated for this, but that also means that there's nothing much to keep your interest. Our big bad wolf wants to encase Christmas presents in thick plastic, turn around and force kids to buy the solvent for it and make them buy their Christmas presents. Comet is horrified, scoops up the rag doll duo plus their rag doll pooch, and jets them back to the North Pole where they talk the big bad wolf into being good? Then have a Peter Pan stage show moment where they ask the children watching to scream along with them? Look, it's weird and obtuse.

Some of my aversion to this could be that I never "got" the appeal of Raggedy Ann and Andy. There's just not much dramatic potential there with these characters. They're so impassive and nondescript that Jones has to inject some borrowed lunacy from his more famous creations to liven things up and that only goes so far. The Great Santa Claus Caper is justifiably forgotten and regulated to a mere curiosity in the collected works of Chuck Jones.

Raggedy Ann and Andy in The Pumpkin Who Couldn't Smile

The narrative stakes in these Raggedy Ann and Andy specials are just bizarre: impossibly low but lacking in a certain sparkle of interest that you begin to pay closer attention to the fact that none of it makes sense. And that's taking into account that you've agreed to watch a cartoon about two sentient rag dolls with a rag doll dog that does extreme sports.

Frankly, I'd rather spend thirty minutes watching Raggedy Arthur skateboard across the time warped village while interacting with the emotionally hysteric pumpkin of the title. At least the pumpkin has a personality more interesting and prone to dramatic overreactions that put the anemic characteristics of the leads in a harsher light. Look, the pumpkin crying seeds and acting like his fate is worse than death amused me. That's really all I ask for in these things.

So The Pumpkin Who Couldn't Smile is a step up from The Great Santa Claus Caper, but only a minor one. There's still the problem of the narrative just not being terribly interesting enough to handle a full thirty minutes (ok, so it’s actually about twenty-two when you remove the commercials). The rag doll siblings notice an unhappy little boy who lives with his cold spinster aunt, so they decide that he needs a pumpkin to restore the spirit of the Halloween season. I don't get it either, but we get a melodramatic pumpkin riding across town on a skateboard to the complete bewilderment of the townspeople.

If The Great Santa Claus Caper looked more Chuck Jones than Johnny Gruelle, then The Pumpkin Who Couldn't Smile jettisons the final vestiges of Gruelle's work for more of Jones. Aunt Agatha looks like any of the older granny characters in a Tweety Bird cartoon, and the pumpkin is all Jones' trademark angularity and rubbery movements. And I would be lying if I said Jones didn’t manage to wring the slightest bit of empathy for me during the emotional uplift ending. It was minor, but it was there. Or I'm just a big softie at heart, either way it worked.

A Chipmunk Christmas

Despite growing up during the 80s resurgence of the Chipmunks, I was never much of a fan of their helium voiced harmonies and sitcom-level shenanigans. I didn't hate them (I still don't, although I don't recognize the grotesqueries they've been turned into by the modern live-action films), but re-visiting them here I felt a sense of beguiling innocence. The narrative stakes are low, Alvin is sweetly naughty, Dave is grumpy and ruffled throughout, and the creative team works in harmony to achieve a solid effort. Perhaps it's that Ross Bagdasarian Jr. had such a strong presence behind the scenes that this special feels like much of the older Chipmunks work. The look and sounds of the late-50s original works marry to Chuck Jones' style very well, and Jones' gentler side comes out in full force.

Christmas specials can sustain a certain amount of schmaltz, and A Chipmunk Christmas piles it on thick with the running plot about a sick boy who is only cured when Alvin gives him his gold harmonica. But I'd be a liar if I tried to proclaim that the sappy, happy ending didn’t earn a smile from me. Maybe I'm just a soft touch underneath the layers of sarcasm and cynicism.

It doesn't hurt that A Chipmunk Christmas looks quite pleasing to the eye, with Jones' quirky character designs being appropriately bouncy and mobile, and Toby Bluth's backgrounds being warm, inviting creations. The soundtrack is also quite strong, with a pleasant mixture of secular and religious songs, and an appearance from "The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don't Be Late)" in a scene mimicking the original recording. None of this is to say that it holds its own against titanic holiday specials like A Charlie Brown Christmas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, or loads of the Rankin/Bass Productions offerings. Put this next to any of those and it's slightness becomes an obvious weakness as its limited plotting is good enough for a brisk thirty minutes, but ultimately forgettable.

A Chipmunk Christmas is still an overall success. Obviously, as its solid ratings and warm reception lead to the long-running Saturday morning cartoon, Alvin and the Chipmunks. (If you're a child of the 80s, that theme song just popped into your head, sorry.) Nostalgia may be clouding my vision, but there was something endearing and charming about how simplistic this thing was. It's a perfectly pleasant way to spend thirty minutes once a year, and sometimes that's good enough.

COMPILATIONS

Bugs and Daffy's Carnival of Animals

Warner Brothers had ceased production on new Looney Tunes material by the mid-60s, but classic characters never die. Through repeated viewings on television, a series of compilation films highlighting their greatest directors, and the occasional lone out to other studios for limited use, the characters maintained their popularity. A series of TV specials began rolling out in the late 70s/early 80s, bringing back titans like Chuck Jones to take the characters out for original productions.

The first special of all-new Looney Tunes material was Bugs and Daffy's Carnival of the Animals, a live-action/animation hybrid that premiered in 1976. This plays directly into a long-established tradition, the never-ending rivalry between Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny, with a backdrop of classical music and poetry. All of the ingredients are there for a successful reunion.

Bugs and Daffy's Carnival of the Animals is a strange mixture, playing like a screwball variation of Fantasia's Mickey Mouse and Leopold Stokowski's brief time together. Whereas Disney took its classical pieces as a vague impression for their imagination and artistry to takeover, Carnival of the Animals takes its title literally, presenting a series of shorts animating the various animals mentioned.

The lions look like a young child's drawing come to life; the chickens like a country kitchen's artwork in movement, and the kangaroos are blocks of solid colors leaping across the frame. It never feels particularly like a Looney Tunes product, despite the presence of Bugs, Daffy, and Porky Pig, but it's still hypnotic in its oddities. The "Birds" section is a particularly surreal highlight allowing Chuck Jones to engage in something that wouldn’t look entirely out of place in Yellow Submarine.

As a Looney Tunes piece, it's heavily disappointing and a bit of a bait-and-switch. Taken as something else entirely, a freestanding work in which these characters merely cameo, it's a beautiful thing. The music is well performed and orchestrated, the animation is kooky and inviting, and gives Jones a chance really experiment. It’s worth a look both for curiosity's sake and for its visual strength. Just don't expect any of the typical anarchy associated with Bugs and company.

Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales

Not only do we get Chuck Jones’ involvement in 1979’s Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales, but Friz Freleng, another one of Termite Terrace’s genius directors. Usual suspects and big names like Bugs, Daffy, Poky, and Yosemite Sam are here, but the presence of Foghorn Leghorn, Taz, and Speedy is most welcome.

The anthology structure of the short means its filled with highs and lows, but at least we get the lows out of the way quickly. A Christmas Carol has been adapted straight, sideways, parodied, and reinvented every which way that it’s hard coming up with fresh jokes or angles into the story. You’d think Bugs Bunny playing merry prankster against Scrooge (here embodied by Yosemite) would be a laugh riot, but it merely raises a few mild laughs. It starts strong but quickly fizzles before rushing to the well-known climax.

The second segment features Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner running through a typical yarn, this time with the desert covered in snowfall and pockets of ice. These two never fail to make me laugh, and this is a good enough run through for the two. But it's the final segment, a variation of "Twas the Night Before Christmas" featuring Taz dropping in on Bugs and his nephew, Clyde. Watching Taz eat everything in sight and Bugs continually outsmart him is one of my simplest pleasures in life.

There's nothing groundbreaking here, but that doesn't mean it’s not entertaining. Spending time with these characters is always entertaining. There are infinitely better Christmas specials out there, but watching Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales is still a perfectly solid way to spend thirty minutes come December.

A Connecticut Rabbit in King Arthur's Court

More commonly known as Bugs Bunny in King Arthur’s Court as subsequent airings gave it a brand new title, but no matter what you call it this is a solid thirty minutes of laughs. Here we find Chuck Jones taking Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court as building blocks for Bugs Bunny to let loose with his smarmy humor, with Daffy as the king, Elmer as a knight, and Yosemite Sam as Merlin. That’s quite a few stooges for Bugs to cause havoc upon, and so he does.

While there’s nothing here that’s anywhere near as funny as the heyday, but still worth a viewing for a series of good chuckles to be had. These guys really knew how to take some recycled jokes and material and make it play successfully. Bugs using his modern knowledge to trick everyone into thinking he has magical powers play right into his smartass charm. A scene during a knightly duel where he comes barreling out on a tiny horse plays like an inverse joke of the obese horse in "What's Opera, Doc?" And Porky as a babbling squire is charming, as his stammering allows Bugs plenty of chances to deliver wry zingers and fourth-wall breaking humor. The joints may be a little stiff, but A Connecticut Rabbit in King Arthur’s Court still charms.

Bug Bunny's Bustin' Out All Over

Another year (1980), another special centered around a unifying theme (spring, this time). Bugs Bunny hosts the in-between segments of three new shorts. All of these specials feature animation that’s a step down from the glory days, but never is this more apparent than in the first segment. A bit of kitsch that finds Bugs and Elmer feuding as kid versions, and feels more like a trial run for Tiny Toon Adventures than anything else. A cameo from Wile E. Coyote asking Elmer to move out of the way for a proper demonstration in falling from great heights elicited a guffaw from me, but the rest is a bit limp.

Next up, Bugs gets kidnapped by Marvin the Martian as a playmate for his pet, Hugo the Abominable Snowman. I wonder how many people get that Hugo’s vocal mannerisms and gullibility is based on Lon Chaney Jr.’s performance in 1939’s Of Mice and Men. It’s an obscure reference, and much of this segment is spent with Bugs conning Hugo into doing his dirty work and not enough of it with Bugs harassing Marvin. Too much wasted potential here.

The ending of the first sequence hints at the final one, as Bugs wonders if he and Elmer started their lifelong chase at an early age, only to find a coyote pup chasing a roadrunner egg. Wile E. Coyote falling off a cliff or smacking into a large rock never fails to amuse me. It’s stupid to be sure, but I never claimed my funny bone was entirely sophisticated or too demanding. This is easily the best segment, and a strong way to close out the show.

Bugs Bunny’s Bustin’ Out All Over is undoubtedly the weakest of the four TV specials I could get my hands on. A weak affair that’s more miss than hit. Temper your expectations with this one, as even the weakest of Looney Tunes properties from the old masters can still provide some easy laughs.

SHORT FILMS AND FEATURES

"The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics"

In 1963 Jones took over Tom and Jerry and ended his tenure with that duo in 1967. This period was is recalled as a "love-it-or-leave-it" one due to criticisms of Jones trying to transform that duo into Looney Tunes proxies, and Jones decided to expand his artistry with "The Dot and the Line." This short would win Jones his lone competitive Oscar. (The Oscar for Best Animated Short used to go solely to the producer and not the director, this has since changed.)

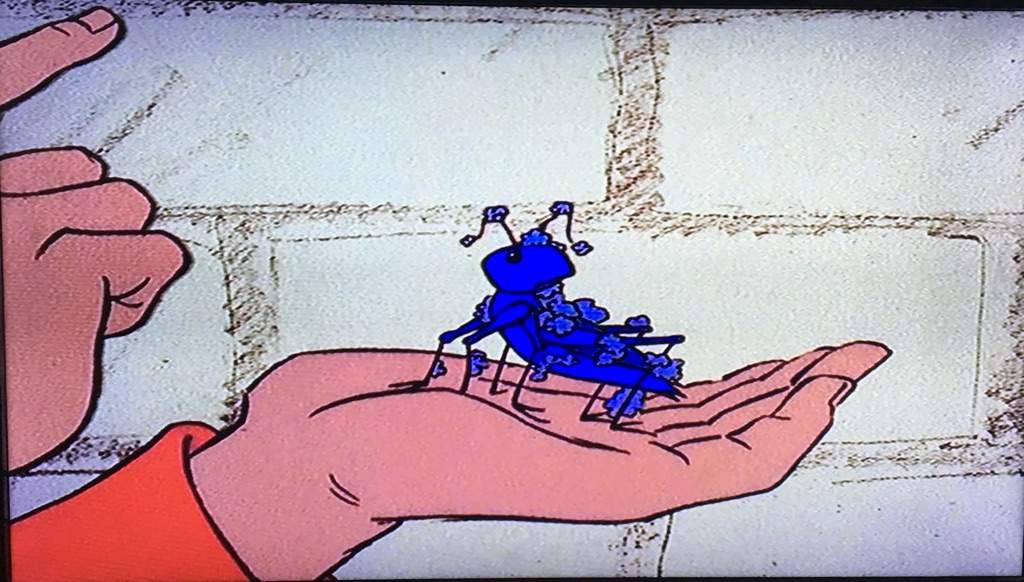

The most immediately evident difference between his beloved Looney Tunes work and this strange little short is the sense of complete abstraction at play here. Lacking any recognizably human characters, Jones uses splashes of bright colors and geometric shapes, backgrounds that swirl and constantly change patterns to tell us the emotional journey of a blue line, a pink circle, and a black squiggle. What's strange about it though is just how easily he manages to pull it off.

"The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics" does feature a heavy-handed narration by Robert Morley, essentially reading large passages of Norton Juster's original text. Yet the sheer excellence and exuberance of the animation allows us to skip past that and focus our attention on the beauty and strength of the technical skills on display. There's also a naughty bit of subtext, as the pink circle rolls around with both the black squiggle and the rigid blue line, coupled with the narration detailing the tortured romance, and it all paints a strange picture of erotic geometric sensuality. That's not even taking into account the color-coding on display here, or the sheer lack of subtlety in making the female figure a warm circular object and the male a hard, rigid one. Very cheeky Mr. Jones, very cheeky.

"The Bear That Wasn't"

MGM's final short film and penultimate animated project, "The Beat That Wasn't" is a loose adaptation of Frank Tashlin's book. Tashlin and Jones first met back in the Termite Terrace days, and this short was a subject of contention between the pair. Tashlin was unhappy with what Jones had done in adapting his book, and the tension between the two is obvious throughout.

Tashlin's jaundiced point-of-view produces some great jokes about corporate culture and identity crisis but Jones was never that dark in his soul. It is an entertaining short if somehow prone to leaving behind an odd aftertaste. It is ultimately a glimpse at two different artists obsessions and styles merging uneasily with one another to produce something strange and wonderful, sloppy but endearing.

The Phantom Tollbooth

Here's an underrated and barely known quantity in Chuck Jones' career. His lone feature-length film, The Phantom Tollbooth is his second dip into Norton Juster's work, but with less explosive results than the adventurous "The Dot and the Line." It's still a very enjoyable and enjoyably strange effort, but there's the persistent feeling that something is missing here.

Normally any film withheld for release for a prolonged period is a red flag. Like, an immediate one with no possible other interpretation than the studio saw the finished product and knew it had something questionable on their hands. The Phantom Tollbooth is an exception that proves the rule for a majority of its running time, even if some spots are sluggish and a certain amount of verbal wordplay and wit is buried beneath a series of visual jokes.

Perhaps another problem with The Phantom Tollbooth is a two-headed flaw that similarly lingers over many adaptations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It is both an insistence on teaching moral lessons in a loopy story of word play and gleeful mischief, and a flabbiness that settles in when you realize the story is merely a series of odd sketches strung together. In fact, The Phantom Tollbooth frequently plays like an agnate variation of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Perhaps another problem with The Phantom Tollbooth is a two-headed flaw that similarly lingers over many adaptations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It is both an insistence on teaching moral lessons in a loopy story of word play and gleeful mischief, and a flabbiness that settles in when you realize the story is merely a series of odd sketches strung together. In fact, The Phantom Tollbooth frequently plays like an agnate variation of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.Even if The Phantom Tollbooth does give off a vibe of déjà vu, at least it allows for Jones to create a series of wonderfully strange and experimental images. The fact that it was originally completed in 1968 hints at what the images will look like. Yes, much like Yellow Submarine and the general weirdness of Saturday morning cartoons of the era, a certain hallucinatory quality pervades the images. By the time it was released in 1970, a mere two years but an eternity in pop culture, this played like a looser, smarter, kookier rebuttal to Disney's dominating animated features of the era. (Although, much like Disney films of this era, things would only have improved with the removal of the unnecessary songs that slam things to a halt.)

Even better is the solid cast that Jones has assembled for this. Mainstays like Mel Blanc, Les Tremayne, and June Foray are present and accounted for. The appearances of Hans Conried (best known for voicing Captain Hook in Peter Pan), Candy Candido, and Daws Butler (the voice of Hanna-Barbera cartoons) do solid work in their typically quirky and nutty character parts. None of The Phantom Tollbooth would work effectively without Butch Patrick (Eddie Munster himself) giving credible life to a bored little boy looking for adventure.

If the final product is a bit messy, at least The Phantom Tollbooth is a film overflowing with ideas and imagination. It is well worth seeking out as it combines a zesty, poppy vibe with more sophisticated humor into something delightfully odd. It is a solid piece of work, but a few nips and tucks here and there had the potential to push it into the realm of unheralded, underappreciated near classic.

"Duck Dodgers and the Return to the 24 ½th Century"

By 1976, Jones had returned to work under Warner Brothers, and reunited with the cast of characters that made his name. These works were primarily TV compilations or in-between segments for films like The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie. Originally released in 1980 as part of a Thanksgiving special, Daffy Duck's Thanks-For-Giving, and soon spun off and reedited as its own short, this marks the first original Daffy Duck and Porky Pig film since 1965. A direct sequel to the wonderful original, "Duck Dodgers in the 24 ½th Century" from 1953, "Duck Dodgers and the Return to the 24 ½th Century" feels like a familiar childhood blanket.

The warm glow of nostalgia perhaps tints your perceptions of the strengths of this one. Entertaining though it may be, it is missing much of the visual splendor and wit of the original. A few backgrounds retain the same sense of mischief and humor, like the egg-shaped planet's strange omelet looking trees, and a couple of the jokes still snap with smart-ass verve, like Porky making his face disappear after being told to remove the smile from his face.

If the return of Daffy Duck and Porky Pig to new adventures never quite achieves great status, it at least is a very pleasing bit of fluff. Never tainting the allure and love for the original, this sequel is a solidly built if lesser creation. But after fifteen years off, of course things shouldn't be expected to flow as easily or smoothly as they once did.

"Chariots of Fur"

Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner first came back to prominence under his guiding hand in the late 70s/early 80s in a series of shorts for The Electric Company. In 1994, before Richie Rich no less, Jones and his eternally warring creations returned to the big screen in this short. Perhaps it's that Jones created these two in 1949 and he knows how they operate best, or maybe it’s the larger budget he had to work with, I can't say for certain, but this feels more akin to his classic works than anything else. The jokes are rapid-fire, and, more importantly, consistently amusing. Wile E. Coyote getting throw off a cliff by a spring, only for it to pull the boulder down on top of him feels like a gag from one of the 50s shorts, and I mean that as a compliment.

The ludicrous products from ACME, a well-known gag for the Looney Tunes in general but this series in particular, continue here, with increasingly improbable offerings. A roll out highway, lightning bolts in a box, and the standby of a giant mouse trap. The gags pile up on top of each other as we barrel towards the climax, which is perhaps a little underwhelming. It's forgiven as everything that came before it radiates with mirth, charm, and a naughty grin.

"Another Froggy Evening"

1995's "Another Froggy Evening" (which premiered before City of Angels, for some tonal dissonance I assume) finds Jones resurrecting Michigan J. Frog, his creation from 1955's "One Froggy Evening." Whereas the original followed Michigan J. Frog and the lone sucker who found him, this one travels through time. Michigan continually gets dug up and reburied by the descendants of the same man (picture the original sad sack as a cavemen, Roman citizen, American revolutionary and you've got the idea), still refusing to entertain for anyone but him. It moves at an amusing clip, but feels somehow missing a certain spark that radiates from "One Froggy Evening."

Not to say "Another Froggy Evening" is bad, far from it, it’s absolutely charming and silly. There’s a series of amusing cameos (look for Looney Tunes alumni Pussyfoot and Marvin the Martian, along with Jones himself, Gene Siskel, and Roger Ebert), the animation is fluid, dynamic and strong, and the jokes are solid. Perhaps it's the sweaty desperation of the original that's missing, this one feels more eager to smack your funny bone than the earlier one.

"Superior Duck"

Does anyone remember 1996's Tom Arnold vehicle Carpool? Well, another year, another Looney Tunes premiere before a family film. "Superior Duck," as implied by the title, finds Jones returning to Daffy Duck, and his fevered imagination. Here we find Daffy operating under the delusion that he is a superhero, with an amusing cameo from Superman for good measure. The back-and-forth between Daffy and the narrator does go on for a few beats too long, but there's still some quiet chuckles to be had with it. Even at this late stage in his career, Daffy couldn't get any respect. What makes "Superior Duck" shine apart from the two prior shorts is a background that combines Art Deco curves with a pristine, futuristic angularity, this type of world feels completely like the creation of Jones. The myriad of cameos are quite pleasing, but there's just something sluggish about "Superior Duck." The others captured a piece of the manic energy and magic of the originals, and this one feels a bit like a wheel spinning exercise. Still, it's Chuck Jones bringing Daffy Duck to life, and sometimes that’s good enough.

"From Hare to Eternity"

1997 brought about the final Chuck Jones Looney Tunes cartoon, and I couldn't think of a better star than Bugs Bunny for that honor. Jones created many of Bugs Bunny's greatest moments, from the reveal that he's the artist torturing Daffy in "Duck Amuck" to the best animated short of all time, "What's Opera, Doc?" Even sweeter is how the whole thing is dedicated to Friz Freleng, one of the greats of Termite Terrace and the creator of Yosemite Sam, the foil for Bugs here.

1997 brought about the final Chuck Jones Looney Tunes cartoon, and I couldn't think of a better star than Bugs Bunny for that honor. Jones created many of Bugs Bunny's greatest moments, from the reveal that he's the artist torturing Daffy in "Duck Amuck" to the best animated short of all time, "What's Opera, Doc?" Even sweeter is how the whole thing is dedicated to Friz Freleng, one of the greats of Termite Terrace and the creator of Yosemite Sam, the foil for Bugs here."From Hare to Eternity" does several things that Jones excels in: combines a piece of high art (here H.M.S. Pinafore is the building blocks of the story's satire), a hotheaded villain for Bugs to play cool prankster against, machine-gun quick gags, a couple quick cameos (listen for Michigan J. Frog), and propulsive energy. Would it shock anyone if I proclaimed this the best of the four 90s shorts? Doubtful, as everything that makes a solid Jones Looney Tunes short is present here.

If "From Hare to Eternity" fails to live up to the loftiest of heights, it's at least a solid goodnight to a career that began all the way back in 1938 with "The Night Watchman." Many artists just stopped producing, hanging it up and descending into distinguished elder statesmen, and one has to admire that Jones' refusal and desire to create. He kept creating right up until the end, his imagination still furtive and active, his humor still sly and impish, and his ability to create solid cartoons enviable. He was a master doing solid legacy work here.

His last completed project was a flash cartoon starring a character called Thomas Timber Wolf. The thirteen episodes of the series premiered on the Warner Brothers site in 2000, and Cartoon Network repackaged his work specifically as The Chuck Jones Show between 2001 and 2004. Jones passed away in 2002 at 89 leaving behind an impressive body of work that ranks with the best of cinema. Perhaps the best words and images to leave this essay with is that of Jones receiving his Honorary Oscar. Between Robin Williams impassioned speech to the standing ovation to Jones' humble acceptance, it is a fabulous summary of a titan.

My Essential Viewing recommendations:

"The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics"

How the Grinch Stole Christmas

The Cricket in Times Square

Rikki-Tikki-Tavi

Mowgli's Brothers

Mowgli's Brothers

Comments

Post a Comment